Safety’s 7 Deadly Delusions & 7 Realities

Safety performance in many companies and industries has stalled in the past decade. Incident rates are at a plateau and, yet, serious incident and fatality rates are not. In more dramatic cases, such as in the BP Texas City refinery disaster, organizations can suddenly experience a catastrophic or multi-fatality event. Analyzing the causes of such inci-dents provides insight into the events and deficiencies that preceded them. But what are the common features in these organizations’ mind-set or culture? What characterizes these organizations’ decision making and their approach to safety and risk, and can features be delineated? Organizations may experience calamities not because they are bad or unsafe, but because they are too safe.

Black Swan Events

On July 6, 2013, in the small town of Lac-Mégantic, Quebec, a train disaster killed 47 people. The incident had many strange precursors or so-called “black swan” events that have occurred in many different industries. Black swan events are rare; there is a minute chance that they will occur and zero chance to occur again in exactly the same way. But, they are so calamitous that the responses are emotional and irrational (but necessary), and in those responses, the seeds for additional black swan events are put into place. The same things in the culture that make it successful may also cause disaster. One such black swan event was the Piper Alpha oil rig disaster, which killed 167 men in the North Sea on Sept. 6, 1988. It was one of the most pivotal events in safety. It resulted in new legislation, textbooks and a critical self-examination by the oil and gas industry. An explosion and fire occurred when a pipe started leaking gas and ignited. A temporary flange with no safety valve was used to block off this pipe during a previous shift’s maintenance opera-tion. The permit to advise operators not to start the pumps on this line was misplaced.

Several deficiencies, problems and system failures coincided. A key factor was that the water deluge system was inoperable at the time and failed to extinguish the large fire that erupted followed by an even larger gas explosion. Most victims were killed from smoke inhalation at the accommodation unit, which was situated on top of the oil rig, where workers had gathered to wait for instructions that never came. The events and the associated system failures are all relevant in the incident analysis, and provide the only insight into what caused it. But, much deeper inside the organization’s culture laid more dark matter. The first inclination is to ask what was deficient in the culture. Did the company’s culture put production decisions before safety considerations? Did it coerce supervisors and employees to ignore safety precautions?

Organizations may experience calamities not because they are bad or unsafe, but because they are too safe.

Indeed, the company had many deficiencies in its systems and procedures, such as the permit-to-work system. But, some questions remain. How was the rig considered one of the company’s most productive and safest in the North Sea? How could this rig win a safety competition 6 months before the disaster, with the deficient permit-to-work system named as its most outstanding system? It was not because of a poor audit. Systems in safety are often like that: operating perfectly when audited, but normally deviated in practice. More tellingly, when asked about the deficiencies, why did the rig manager say, “I knew everything was all right because I never got a report that anything was wrong” (Brian Appleton presentation, video recording). This is a strong indication of a delusion. The manager was deluded that his rig was safe, sound and well managed. His confidence was based on absence of reports about problems. Most managers agree that one must rely on reports and trust empoyees, as this allows managers to expedite work. It is an integral part of the success of the business, which is now identified as a cause of the failure.

But, what if workers do not trust the manager? What if they feel that reporting deficiencies will result in their becoming the targets? What if workers do not want to disturb the peace in a company that is doing well on safety, with no incidents? The culture in such an organization is not deficient in the traditional sense — it is deluded. A series of such delusions has been identified in the author’s research. Peculiarly, the industry disasters during 1980 to 1999 tended to be at mine sites that could hardly be described as deficient in their safety management. They were operated by mining corporations that had a sincere focus on safety. Indeed, one such mine was North-parkes gold and copper mine in New South Wales, Australia, then owned and operated by North Mining, a mining corporation long regarded as a leader in safety in the resources industry in Australia. During the day shift on Nov. 24, 1999, four men were killed at the Northparkes E26 Lift One underground mine as a result of a massive rock collapse and subsequent devastating air blast. While the incident investigation focused mainly on the risks and technicalities associated with so-called block cave mining, there was a unique opportunity, unreported until now, to also study the mine’s safety culture and systems.

At that time, the resources industry of Australia presented the Minex Award to the best mine from a safety perspective, after a rigorous audit and analysis of the mine’s safety systems, culture and performance. Northparkes was given a “high commendation” by the Minex panel prior to the disaster. Also, in 1999 the Australian Minerals Council commissioned an industry-wide safety culture survey. Northparkes Mine was also a participant in this. The author’s company, SAFEmap, was responsible for the survey and subsequent report (see www.safemap.com). Northparkes was a top-performing mine in safety. The survey of safety culture had placed it as the third highest in the rank of positive responses by employees and the safety culture was unequalled. The Minex panel gave the mine a high commendation in the awards process that same year, and 4 months later, the disaster occurred. Suddenly, the search was on for what the company did wrong or did not do at all. It became a broken company. It is suggested that mine management was not deficient, it was simply too good for its own good. The huge focus on safety, the achievement of lofty goals and celebration of safety successes led to a mind-set that safety leaders were protected by an extraordinary safety system and that the safety incident figures indicated a truly world-class safety performance.

Seven Deadly Delusions

The evolution of these delusions is not a linear process. The analogy of a whirlpool might illustrate the process. At the surface, near the edge, the slow swirl of water appears normal and mundane. As the movement gathers momentum, it increasingly becomes powerful and erratic, and randomly draws more debris toward the center, which collides and bounces unpredictably. The typical organization shows the same patterns of movement and may continue to swirl with no negative effects until a random event triggers a series of random connections, nodes and ripple effects, then a powerful collision results. Organizations and managers have long been the victims of myths and delusions and so has the science of safety. Many slogans and mantras abound in the safety profession and large industries evolved around those. Myths such as “human error is the root cause of incidents” and “all hazards can be controlled” have long been part of the foundational concepts of safety management.

1) Causation

A key aspect of modern risk management approaches is that risk has a certain probability (likelihood or chance) and if the risk is analyzed, its probability can be identified and precautions taken. However, unlike the risk insurance industry, little objective, hard data are available about events in near-zero organizations. There simply is not enough data to achieve the goal of risk quantification, and risk assessments can become a subjective guess often performed by unqualified people who have a vested interest in a certain guess or who are easily manipulated for organizational politics. It creates the delusion that risks are quantified, which was exactly what happened in the case of the Space Shuttle Challenger. The delusion of causation is further entrenched by incident causation models created by Heinrich (domino theory) and Reason (Swiss cheese) that create the impression that incidents have rather simple, linear traces of failures in defenses that allow them to occur.

A further delusion is that strengthening defenses will prevent the linear causes of incidents. It could not be further from the reality of failures. With the complex and chaotic nature of risks, the randomness of these failures is impossible to predict, yet very simple to review. This delusion can also be named the delusion of predictability — that all events could have and should have been foreseen. The common phrase “an accident waiting to happen,” is all too common. The investigation becomes condescending, and the business operators have no defense, because the fatalities make it indefensible. Those operators dare not divulge that the signs of incidents were always there. Many complex factors exist in the business that the operators do not and cannot control, other than to shut that business down. In safety, we simply do not have or we do not employ advanced techniques of risk scanning. The analytical methodologies with which we look at incidents can have only one outcome: it is a series of easily identifiable errors and failures.

We apply risk management techniques still based on the Taylorist models of management, which are more than 100 years old, in the modern complex adaptive systems that organi-zations have become. We use management techniques originally designed to build Model T Fords to launch space shuttles into space.

2) Compliance

James Reason published an insightful article in 2001 in which he made the controversial statement, “Following safety procedures has killed people,” and he cites examples such as the Piper Alpha disaster in which the workers who strictly followed the safety procedure were the ones killed in the fire, while those who jumped into the sea against procedures survived. This does not imply that safety procedures are wrong and should not be adhered to, but it does mean that human beings in a high-risk work environment should first apply their risk skills and risk judgement. While complying, humans become less responsive to the threats, or signals of such threats, in their environments. The lack of attention of a pedestrian at a crosswalk underscores this. Several other influences are at play in this delusion. The reliance on workplace procedures and rules readily becomes cult-like and workers are increasingly confident that the safety system is reliable and trustworthy and, therefore, show less inclination to deviate from company directives, even if the actual situation of impending risks may dictate otherwise. Organizations also act in the same way when they believe that their safety system audits show impeccable results. Their commitment to safety is clear and unequivocal and their measured performance proves it.

3) Consistency

Humans learn to deal with risks through a complex process of cognitive adaptation, often developing an intuition and competence that defies reasoned thinking. This capability allows them to handle risk in a highly variable manner with a readiness for many possibilities. But then, risk control logic says we should limit all variability and create consistency and compliance in the workplace. Workplaces are becoming increasingly regulated by numerous rules, controls and legislation with the natural increase in perceptions of predictability and harmonization of work practices. This logic seems flawed and contrary to the natural state of any high-risk and complex system, where risks emerge dynamically and systems adapt to interventions. It is also deluded to think that we can impose consistency because of the sheer inherent and chaotic nature of organizations. The power and benefits of human performance variability and responsiveness increasingly becomes lost.

4) Risk Control

The delusion of risk control is the most persuasive and attractive. In the OSH profession, we create myriad rules and procedures that are supposed to defend workers and create controls in the workplace. These are the basis of most legislation and are often supplemented by management. Many organizations have comprehensive safety management systems in place, either based on a commercially available package, or they deploy their internally developed and audited systems. Organizations that had disasters (e.g., BP, Union Carbide, Occidental Petroleum, NASA) all had a focus on risk control, not unlike the focus of other nondisaster organizations such as Shell, Dow Chemical, Chevron and Aérospatiale. All have well-developed systems and operate sophisticated auditing of compliance. A key element of these systems is

a clear, unabated focus — to control risks at work. While these systems are largely successful, they eventually become a complexity of their own. Layer upon layer of risk controls actually create behavioral responses that expose the organization in unpredictable ways. The organization does not and cannot cater for the risks that migrate for new risks created by the risk controls themselves, or for the natural response of humans and organizations, to adjust their risk thermostats accordingly. This risk homeostasis occurs when the more we perceive risks as being controlled, the more we increase our risk propensities because we believe we are so safe.

5) Human Error

The delusion of human error is closely linked to stereotypes about OSH professionals and to the delusions already noted. A long-standing axiom in behavioral safety is that most incidents occur because of human error and that behavioral observations will eliminate this. This linear approach underestimates the complex interactions between humans and their dynamically changing environments. It also misses the point that human actions are only the visible sharp end of the many safety management systems that create and induce human error. It also misses the point that human error is a misnomer. The notion of human error is so entrenched in the safety literature that it is almost incomprehensible to argue that it does not exist, that it does not cause incidents or that human error itself is a symptom of a system. But human error is inevitable; it is part of the human condition and a necessary part of our survival as a human race. A human race that is completely situationally aware, vigilant and focused on all risks in their environment, even minute ones, 100% of the time, will not survive mental breakdowns. Safety has a focus on behavior and behavior change entrenched in its paradigms, yet, behaviorism is an outdated concept that is too narrow a paradigm to describe human nature. The world has moved on and safety science has stayed behind. Human error is cognitive and largely unintentional. How then can attempts at behavioral management, which fundamentally assume that risk taking is intentional, have any effect?

6) Quantification

A significant demand exists for improving safety performance, as measured by graphs and statistics, which results in various treatments of the data. Workers are quickly rehabilitated to return to work before a certain cut-off period, incidents are argued away as not work-related or large incentives often drive down the rate of incident reporting. Not only are the data unreliable, they are also invalid. The reality is that the small number of incidents at the top of the triangle simply cannot be a measure of safety. In most organizations, numerous activities take place every day and if only one of those activities fail, or 10, the statistical insignificance is the same. Yet the OSH profession thrives on measurement, and it may well be the primary cause of calamities and lead to the killer delusion of invulnerability.

Another delusion is that minor incident ratios are predictive of serious events. Ratio triangles continue to pervade the profession and professionals chase after the reporting of small incidents or near-hit events in the mistaken belief that trends in these will allow them to prevent serious ones. While there may be value in learning from these failures, the patterns and trends are false and misleading. We gain no insight into catastrophic system failure from knowing the frequency of soft tissue injury or infractions of personal protection usage. The most damaging delusion is the obsession of the industry with the notion of zero (incidents or harm) that can trigger failures. The focus on zero triggers a failure in creating a just culture, because a zero tolerance approach soon follows. Normal deviations and variability in system performance are viewed as abnormal and are treated as such. Under those circumstances, the trajectory toward zero incidents suppresses information about mistakes, risks and potential problems, and triggers the ultimate failure of risk secrecy. Many, even most, disasters in organizations were preceded by excellent safety performance and an obsession with safety metrics. Therein lies the ultimate harm; the focus on incident numbers is inherently flawed.

To achieve zero fatalities, we must achieve zeros in all of the contributing factors and causes, such as mistakes, system failures, deviations, human errors, hazards and risks. Eventually, a nirvana of perfection is pursued, which is a condition that is only imaginary. To achieve a reduction in zero incidents one must reduce (eventually to zero) near-hits. However, we must encourage the reporting of near-hits to identify and eliminate the risk. This results in a process of elimination through nonreporting. At best, this is self-defeating; at worst it is fatal. The target-zero philosophy also sends a misguided message to the entire organization: that the safety journey will one day end in a decisive victory. It is a false victory. In the end, safety metrics become the goal itself, and this distorted focus will eventually kill the business. For example, it is quite possible to achieve a zero fatality goal, and a wor-thy one, too. In North America, more than 30,000 people are killed in traffic incidents per year. Solution: Change the speed limit on all roads, everywhere, to 5 miles per hour. Finally, the zero-harm discourse introduces the biggest force of destruction into the organization, namely fear. It is perhaps target zero’s most damaging consequence. The lengths to which organizations will go to achieve the required performance numbers is astounding. For example, some companies are known to hide serious incidents routinely from clients out of fear of losing work contracts, and ordinary workers hide injuries to escape being scape-goated a few days out from another zero-days milestone. It had been reported in the British press that construction companies in Doha, Qatar, would transport the bodies of deceased contracted workers from building sites to their country of origin, where they are reported as a fatality on another work site of that sub-contractor, allowing the main company to then report another year with zero fatalities. Of course, not all companies engage in such extreme behaviors, but many still do it for lesser injuries.

7) Invulnerability

Like Titanic, the delusion of invulnerability is the most deadly. It pervades the minds of all and eventually becomes ingrained in the organization’s culture. It is caused by three factors or conditions in the organization: 1) high levels of perceived safety protection of systems and programs; 2) low levels of incidents occurring (near zero); and 3) the increasing trend of workers, supervisors and managers to hide risk-taking, risks and potential safety problems from the critical eyes of managers and safety professionals. This is largely a result of a well-intentioned, but poorly deployed, focus on zero. Most organizations that suffered dramatic disasters had commendable safety performance records. Apart from the fact that these statistics are unreliable, the actual decrease in incidents also creates a reduction in the organization’s ability to maintain a state of risk readiness: the signals are fewer and weaker, and therein lies the ultimate dilemma. The OSH profession relies on these signals because its science is created around finding error and failure, and analyzing and eliminating them. It has few predictive or progressive methods, and it has little understanding of statistical analysis of the small kind. It uses statistical techniques such as moving averages and frequency rates to make predictions that are wholly inadequate for the kind of weak data sets it has.

The safety profession cultivated the vision of zero incidents and often criticizes those who question it. While zero is the only moral target for any company, the answer of safety lies beyond the numbers, certainly not in the absence of incidents. The delusion of invulnerability is often incorrectly described as complacency. Training programs suggest that the problem is the workers who fail to keep their minds on the jobs, who rush or who display poor attitudes (of com-placency). OSH professionals declare “war against human error” and we plug holes in the Swiss cheese layers. As we achieve the targeted reduction in the numbers is achieved, we confidently conclude that we are near victory, but we have set ourselves up for the moment when all things evil come together, when a simple mishap links with another, and an explosion, fire or chemical reaction results in the deaths of many. That is the inevitable conclusion of the delusion of invulnerability, but only if it actually happens. Most organizations may be harboring the same delusions, but escape the calamity, not by design, but by sheer coincidence and good fortune.

One of Albert Einstein’s most meaningful quotes rings true here: “The world we have created is a product of our thinking; it cannot be changed without changing our thinking.”

Leading Safety Into the Future

The seven delusions each give rise to a new reality for managing safety. In these new realities, the safety profession disappears, just like the quality control profession disappeared because it became fully integrated into basic operational processes. It is time to abandon the behavioral era of safety and embrace the new era of resilience engineering. The safety professional has a new role as a resilience engineer who increases the effectiveness of the organization.

1) From Delusion of Linear Causation to Reality of Systemic Complexity

In the old model, the organization is seen in a simplistic way — as a technical system in which any event has a cause, and every cause has another cause, until a root cause is found. Analysis processes are based on the original domino models of Heinrich, and even though we have smarter Swiss cheese models, they are still linear. The original root cause is the need for the organization to take risks, because without doing so, the organization will not exist, nor succeed. We cannot eliminate the root cause of incidents. Complexity refers to the fundamental paradigm of organizations as complex sociotechnical systems, with interactive layers, tightly coupled processes and complex goals. Organizational structures are flexible, intertwined and dynamic. In this reality, the traditional safety approaches and tools are invalid, inadequate and ineffective. Existing safety techniques of incident analysis should be reconsidered, and new ones found that can capture this reality of multiple and dynamic causation.

2) From Delusion of Compliance to Reality of Adaptation

Flexibility of operational systems ensures the ability to quickly respond to changes and to maximize profitabil-ity or effectiveness. Directly contrary to this is the rigidity of the safety/risk management systems that are currently deployed, coupled with legislative requirements that demand compliance at all levels. Particularly because of legal considerations, organizations have become cult-like in the culture of compliance. These cultures do not allow for innovation, flexibility or adaptation, and in fact, destroy it. In the new reality, safety approaches allow frontline employees the latitude to make crucial decisions and responses at the point of risk, even allowing them to bend safety rules where employees judge this to be safer. Safety systems are adapted to the operational realities, instead of operations adapting to safety systems. This will require high skill and competency levels in employees and extremely high levels of trust at all levels.

3) From Delusion of Consistency to Reality of Variability

Consistency is the foundation of all organizations, because it delivers a predictable range of controlled operation, and variation is the enemy of safety, efficiency and quality. But, the range has become too narrow in the near-zero organization. With this myopic focus on safety deviations and shortfalls, the absence of variability has defeated innovation. The organization has lost its innate capability to renew processes and to push them to the next level. The safety profession was too successful. In the new reality of variability, innovation is the new focus. The prevention of incidents is no longer based on the hierarchy of risk controls, but on the capacity to change and innovate fundamental processes, and to solve risk at the source. In this reality, an organization’s operational systems are dynamically changing and responding to risk. There are no bolted-on safety regulations for each task because each becomes inherently safe and efficient through adaptive innovation.

4) From Delusion of Risk Control to Reality of Uncertainty

The control of risk is hardly ques-tioned. The science of risk management enjoys growth and self-confidence in the safety era, because it promises to identify, evaluate and mitigate risks. In an immature work environment, with high levels of risk and incidents, the science can probably deliver good outcomes. But in a mature environment, at near-zero levels of safety performance, the existence of risk is not obvious anymore, because previously, the occurrence of incidents identified the risks. But the absence of incidents should not be taken as an indication of the presence of safety. The new risk system has a human risk control hierarchy, long before it contemplates its engineering controls, such as elimination or substitution, or its administrative controls. Humans have several options to control or respond to risks, such as proceed with caution, review tasks, change methods, incorporate assistance, seek expertise or elevate decisions to the supervisor as the risk levels increase. The new risk management is focusing on risk resilience in response to uncertainty — learning, responding, monitoring and anticipating, all in real time.

5) From Delusion of Human Error to Reality of Competence

Human error continues to be targeted as the (root) cause of problems in safety and humans are still seen as the weak link in the safety chain. Programs to change behaviors, overcome complacency and improve attitudes abound. In the new reality of competence, humans are seen as the strongest link, where people are trusted, skilled and enabled to make decisions, to take risks competently and to contribute to the effectiveness of the business. The new safety system actually relies on the human capabilities, not on mitigating or engineering them out. Humans have immense capabilities such as risk intuition, sixth senses, lighting-fast responses and smart heuristics, which are all dumbed down by the current safety system.

6) From Delusion of Quantification to Reality of Randomness

The notion of randomness in safety science is controversial, even unacceptable. The science is riddled with myths, such as “all incidents are preventable,” “safety is no accident” and “no hazard is uncontrollable.” They all make emotional sense, but can be challenged at a rational level. Randomness is a key aspect of life, risk and incidents. It delivers both good and bad outcomes, and is increasing in its magnitude, or contribution to events. Dealing with systematically occurring risks (if that is the paradigm) in a systematic way seems to make sense, but in this new reality, risks are random, and the treatment must be random, too. An organization’s reward systems should be for effort and for random effort, and no rewarding of safety results as measured by key performance indicators. Traditional safety key performance indicators are invalid and unreliable, increasingly fudged to obtain targets, and should be abandoned in favor of measurements of impact, such as perception and culture mea-surement, deployment effectiveness, and quality levels and control depth.

7) From Delusion of Invincibility to Reality of Resilience

The delusion of invincibility is di-rectly correlated with increasing success in safety improvement. The near-zero organization has only few reminders (incidents) of its vulnerability and believes traditional measures are to be believed in its own capabilities, systems and defenses. It has increasing evidence of this as incidents rates decrease and the number of days between incidents extends further.

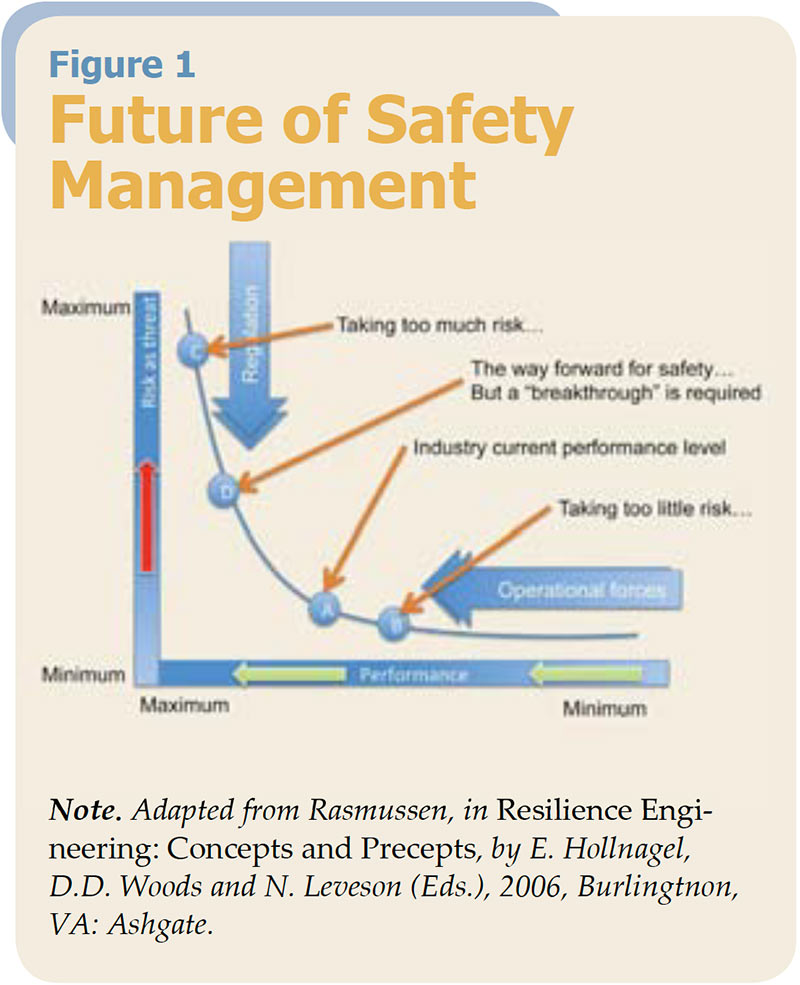

Figure 1: Organizations must develop capacities to take risk competently, rather than avoid risk effectively. This is a different notion to traditional safety management.

Risk systems focus on predictability and control, and the increasing controls reduce the number of incidents, which shed light on potential system failures. Although it is impossible to predict a black swan event, it is possible to prepare for it and imperative to search for it. The absence of reminders of vulnerability hinders a willingness to prepare and shifts the entire business further toward the edge. The ability to suppress volatility, inconsistencies and uncertainty has created system atrophy; it still looks like a system, but it will not have the innate flexibility to respond when adversity strikes. And, when control is lost, coincidence becomes a killer. In the new reality of resilience, the organization develops a capacity to grow from disorder and failures, to know what to look for and to accept error as positive uncertainty. It is the difference of accepting 50 car crashes at 1 mph each, instead of one car crash at 30 mph. The net statistical impact on the organization is the same. It can recover, grow and learn from the small incidents, but will perish from the one big catastrophe. Resilience does not mean the organization is able to withstand or avoid adversity. It means it becomes better as a result of it. The key is to ensure that the adversity is small, limited and readily identified. The problem is that the car crash example does not allow avoiding both. Avoiding the smaller incidents develops atrophy, opening the door for the big one. We must have the small ones to preempt and avoid the big ones. If we avoid the small ones — the focus of current safety paradigms — we will have the big one, un-less we are lucky, and we should not want to take that gamble.

Conclusion

Organizations are currently functioning at an optimal level, given modern constraints and limitations. In Figure 1, organizations are probably functioning at the A-in-tersect. At the C-intersect we will be taking too much risk and killing people, at the B-intersect we are taking too few risks and will go out of business. As safety professionals, our focus should be to move our organizations from the A-intersect, to the D-intersect higher up the risk and performance curve. This will be a challenging concept for most OSH professionals, whose entire raison d’etre is to keep the organization at the lowest risk level possible, and to push the organization toward the B-intersect/lowest risk. Organizations much develop capacities to take risk competently, rather than avoid risk effectively. This is a different notion to traditional safety management. The organization should look like this:

- Variable work practices, developed through local experimentation to be optimal.

- Distribution of decision-making authority to the actors in the local circumstances.

- Technology that enables people, rather than restrains or disables them.

- Operational procedures with safety completely integrated/invisible.

- Random and dynamic interventions, as against structured, reactive safety interventions

It is for this reason that the fundamentals of the safety profession must be reviewed, challenged and redefined. A profession with safety at its heart cannot be expected to be something else, and will always be in conflict with any attempt to move the organization in a different direction. Therefore, safety must be replaced by something else, and that something else could be the concept of resilience. In the organizational context, this could be defined as the department of resilience engineering, whose focus is to create abilities in the organization so that it can:

- Know what to do, that is, how to respond to regular and irregular disruptions and disturbances either by implementing a prepared set of responses or by adjusting normal functioning.

- Know what to look for, that is, how to monitor existing or potential near-term threats. The monitoring must cover both that which happens in the environment and that which happens in the system itself, that is, its own performance.

- Know what to expect, that is, how to anticipate developments, threats, and opportunities further into the future, such as potential changes, disruptions, pressures and their consequences.

- Know what has happened, that is, how to learn from experience, in particular how to learn the right lessons from the right experience including successes as well as failures.

Corrie Pitzer leads a global safety consultancy focused on:

CULTURE CHANGE, DEEPSAFE LEADERSHIP and FATAL RISK SYSTEMS.